‘Selections from the Permanent Collection’ Lends a Public Spotlight on an Impressive Permanent Collection

Fri Nov 07, 2025 | 11:43am

It is possible to think of a museum’s permanent collection as a trove of treasures — some shinier than others — lying in wait, hibernating until its keepers decide to let the light in. Once freed from its bondage and brought out into the publicly viewable open, the outside world can take stock of what’s been lurking in an institution’s vaults.

At the UCSB Art, Design & Architecture Museum (AD&A), through December 7, the in-house collection is more than ready for its spotlight. The show Beyond the Object: Selections from the Permanent Collection joins the ranks of recent collection-airing exhibitions at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and Westmont’s Ridley-Tree Museum of Art granting public access to their impressive holdings.

Curated by Ana Briz, the Museum’s Assistant Director and Curator of Exhibitions, the exhibition reflects recent acquisitions, mostly from within the past five years. Contemporary art is the primary focus, although the star of this show is a striking anomaly. Acquired in 1985, Joan Mitchell’s “Sunflower,” a fairly massive painting, greets the visitor with a rugged panache in the entryway gallery.

The prominent Abstract Expressionist’s canvas, painted in 1970, is a considerable prize of an asset in the museum’s collection and has been brought out in sync with her centennial year. Her points of reference are both art historical and personally nostalgic, having had an influential childhood exposure to Van Gogh’s sunflower series. As channeled by Mitchell, echoes of Van Gogh’s heightened expressive intensity and underlying lyricism are filtered through her vibrant abstracting approach, as if burrowing inside the spirit of the flower, leaving the details ambiguous.

A yet larger painting awaits in the tall-ceilinged gallery inside the museum proper, in the looming vertical form of Rose D’Amato’s “Diamond St. to Ingalls,” a post–pop art meshing of elongated diamond shapes and visions of American liquor store signage kitsch. By contrast, Mona Kuhn’s 2001 piece “Spectral” represents the photography cause in the show, a Man Ray–like nude study bathed in surrealism sauce with overlapping layers and a solarized visual effect.

Nearby, socially charged art — and public interfacing — makes its presence known in the 1988 piece “Welcome to America’s Finest Tourist Plantation,” by Elizabeth Sisco and David Avalos.

The image montage expresses indignation about immigration tensions and racial inequities, and in a provocatively public way — placed on 100 buses in San Diego. The art was met with admiration and support by some, consternation from others. We quickly recognize the keen relevance to current life in the Trump daze.

Artists calling Santa Barbara home have a place in the show, as well. Hank Pitcher’s 2002 painting “Magic Forest, Scrub Jay” is a classic landscape with a cool difference, and Pitcher’s own special painterly voice. Bauhaus-trained artist Herbert Bayer, a Santa Barbaran for his later years, may be best known for his rainbow-colored “Chromatic Gate” sculpture across the street from the beach on Cabrillo. It’s fascinating to see his deft way with color and geometry in a much subtler and more intimate mode, in silkscreen prints at the AD&A.

In another case of appreciating an artist’s work in a radically different scale than what we expect is the screenprint by Jonathan Borofsky, perhaps best known for his sometimes monumental “Hammer Man” sculptures around the world. Here, in an almost blueprint-like format, he envisions a vignette involving stick figures, a crude architectural space, and an enigmatic action betwixt the two. In this case, the mouthful title tells the story — literally: “I dreamed I was having my photograph taken with a group of people. Suddenly I began to rise and fly around the room. Halfway around I tried to get out the door. When I couldn’t get out I continued to fly around the room until I landed and sat down next to my mother who said I had done a good job!”

Diversity of scale, medium, and objectives is the rule in this exhibition, to its credit. In the main gallery, Steve Roden’s four sparse canvases walk the border between realism and the abstracting impulse with an appealing, funky grit of a style, while John Glinsky’s painting “Trip to Topawa” is a trippy, psychedelic convergence of swirling line and color.

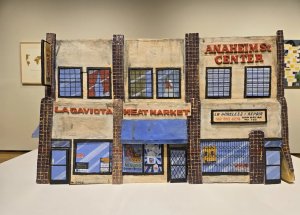

Three-dimensional art may be sparsely represented in this sampler, but a notable entry is Christopher Suarez’s “Anaheim Center,” a compact ceramic-and-paint model of a humble SoCal urban building. The sculpture elevates the everyday to art-worthy and gallery-anointed status.

Incidental thematic threads aside, Beyond the Object fulfills the important function of allowing us into the vault for a good look at what lives there. As seen in this selective slice of vault life, the AD&A’s permanent collection is looking hale and hardy. See museum.ucsb.edu.